KARACHI: Living in the current scenario, it might be easy to assume we’re the offspring of Ertugrul Ghazi, descended from the Turks. No matter how much it may hurt us and the sitting premier, descending from Ertugrul may not be a blessing we enjoy. Our national identity has, for a long time, been extremely confused, fissioned into several components, with individuals taking what they choose. Sometimes several identities come together to create our culture. But the big question is, which ones are we ready to own?

Recently, children who were engaged in swordplay were asked what they were up to. Their reply, alarming to a great extent, showed their association towards an identity they have idolized because of the way the media has projected it.

The ‘appropriation’ of a Turkish warrior culture has been encouraged by none other than the PM himself. Citing it as ‘our history’ the show was telecast on national television for all to see. The prejudice of being superior as a Muslim majority among several strata of the society has not been entirely erased. And once prejudice is allowed to fester, it soon turns into discrimination.

But who exactly are we, and where did we come from?

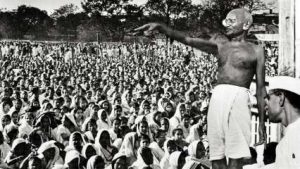

India’s prehistory comprised of Dravidians, ancestors of modern-day Hindus, who also took Vedic transcripts from the Indo-Aryans who later came to India. The Indo-Aryans brought with them Sanskrit, a language that has been the origin of a number of languages, including Persian, Urdu, Hindi, and even English. Along with that, they brought with them a belief system that was quickly joined together in the already existing Dharma.

From this Aryan period to the conquest of Sindh by Mohammad Bin Qasim, several Hindu kings took the throne including Chandra Gupta Maurya and Asoka. The latter spreading Buddhism throughout the subcontinent. In this Hindu land, Muslims were a foreign entity. One of the very first people recorded to have traveled to India was Malik Dinar, a scholar from Persia. Soon afterward came Bin Qasim’s conquest followed by Mahmud of Ghazni (a city in Afghanistan), Muhammad Ghori (another king from Afghanistan), The Slave King dynasty (their roots in modern-day Kazakhstan), Sher Shah Suri (a king belonging to the Pashtun Sur tribe) and the Mughal emperors who came from Persia descending from the Mongols.

Later on, the downfall of the Mughal empire resulted in the British takeover of the Subcontinent and India fell into the hands of the English. We related with the Turks for their Khilafat movement too, protesting here in India when the caliphate was threatened until Mustafa Kemal Attaturk a hero amongst Muslims of the subcontinent turned Turkey into a secular republic after abolishing the caliphate on his own. We all stood still at that moment.

After we gained independence and formed Pakistan, there was a sudden need for a national identity, specifically one that differed from the identity of the Hindus we parted ways from. Pakistan has to be the Nation-State Jinnah had seen it as, even when it divided itself into several. Due to this, Pakistan quickly took up Urdu as its official language, causing a suppressed outcry from various ethnicities that were already geographically located in Pakistan such as Bengali, Punjabi, Pushto, Hindko, Saraiki, Sindhi, Balochi, Burushaski, etc.

The forced unity was in an effort to revise the two-nation theory that the partition could not be avoided at any cost because somehow the only way to live with Hindus was during the 650 years when Muslim kings ruled India before the British took over. This forced unity tried to find (and sometimes enforce) similarities to its people so that India could be seen as the outgroup and the entire Pakistan could form a single unit – the ingroup. During the late 70s, when people started to become more aware of their ethnicities, a vacuum of identity was assumed. This vacuum would later be filled by the Arabization of Pakistan in the late 1970s and early 80s.

Soon after this, several everyday words with a Persian origin were replaced by Arabic versions of them. Iran was the outgroup now. Our new national identity was Arabic. Khuda Hafiz became Allah Hafiz, Ramzan Mubarak became Ramadan Kareem. In her article, Islam’s Lesser Muslims: When “Khuda” Became “Allah”, Alia Ahmed carefully sums up the whole ordeal with the following words,

Pakistan has long been torn between its Indo-Persian roots and the cultural imperialism of a much darker strain of Sunni Islam imported from the Gulf, particularly Saudi Arabia. Though it was Zia who, with the US and Saudi support, set up madrassahs, or Islamic schools, to fund and train puritanical warriors in preparation for a “jihad” against Soviet forces in Afghanistan, the cultural ramifications of his policies polarize the society to this day.

She also quotes Badar Alam, a veteran journalist and editor-in-chief of The Herald, “As Muslim societies in the post-cold war era are increasingly viewing themselves in terms of very literal interpretations of Muslim history and theology, anything that offers a culturally different point of view is shunned and discarded. Language purification is part of a larger purification. Even in Bangladesh, where pride in the Bangla language is part of the national identity, Allah Hafiz is now a common way of saying goodbye. And Persian, after all, is the language of Shia Iran. In a contest between Shia and Sunni Islam, the Sunnis must prefer Arabic over Persian.”

The identity crisis continues, unlikely to stop anytime soon, considering the outsourcing of artists from Turkey, which further accentuates our national amnesia.

Designed by Aamir Khan

Designed by Aamir Khan