LONDON: Playing cricket in England is a unique experience. Club cricket, with its grass roots community feel, lush green fields and curated pitches, has always held special appeal for me. Nowadays, South Asian participation makes up 30% of the recreational game in the UK and 18% of the cricketing economy is contributed by fans of South Asian origin. This means that words and phrases such as shahbash, bohot alla, kya baat hai are often heard on the field of play.

Urdu is the code language you use when you want to communicate with another player without the opposition knowing what you are saying. Although you will occasionally come across a disapproving umpire encouraging players to ‘speak English’, for the most part, amateur cricketers in England enjoy this new flavour blending into their local game.

Every now and then, an Englishman will ask me, “What is Pakistani jazba?” Translating this as ‘passion’ is probably most appropriate, but really, if you haven’t felt it, you won’t understand it. I have always thought that English cricket is too cerebral, too analytical, and too conservative to be able to understand the true meaning of jazba.

Read: The Curious Case of Mohammad Hafeez

Cricket is popular in this country, but it remains somewhat of a niche sport. Finding a cricket fan among the common population is a rare enough occurrence. Mostly it is a joy shared on the weekend with those strange people who choose to forsake their entire Saturdays for a game of amateur cricket, much to the disapproval of their life partners.

However, this is not really an article about cricket. I wanted to tell you that these past few weeks, England has rediscovered their jazba. You may or may not have heard, but since the beginning of the football world cup, England has been abuzz. There was a national conversation afoot, heard everywhere – on trains; buses; in social gatherings; workplaces; coffee shops. In that sense, it was similar to the EU referendum, when the national discussion was palpable – wherever you went, everyone was talking Brexit. But again, this political dialogue was too cerebral, too theoretical, and too conservative to be called jazba.

English jazba only became apparent to me recently, as the nation celebrated their team’s efforts in the football world cup. Englishmen and women, silently ashamed of going over 50 years without a world cup trophy, and as in love with the game of football as Pakistanis are with cricket, were singing, quietly and cautiously at first as England stumbled their way through their first game, then loudly and terribly in unison after their 6-1 defeat of Panama.

Every time, they would be singing the same old song, trying to convince themselves that ‘football’s coming home’. Wherever you went, Baddiel and Skinner’s classic ’96 football world cup anthem, ‘It’s coming home’, could be heard. Everywhere, the collective national temptation to squeeze in the phrase, ‘it’s coming home’ into any conversation about anything was too great to resist. Amusing, strange and diverse renditions of the laddish football song populated the web. On the radio, I heard an interview with a 101-year-old lady who also finally confirmed to her interviewer, in a shaky, meanderingly slow, quivering voice that, surely, this time, ‘It’s coming home’. Everyone was in on it and, if they did not believe, they hoped against hope deep down in their football-obsessed hearts. True national jazba.

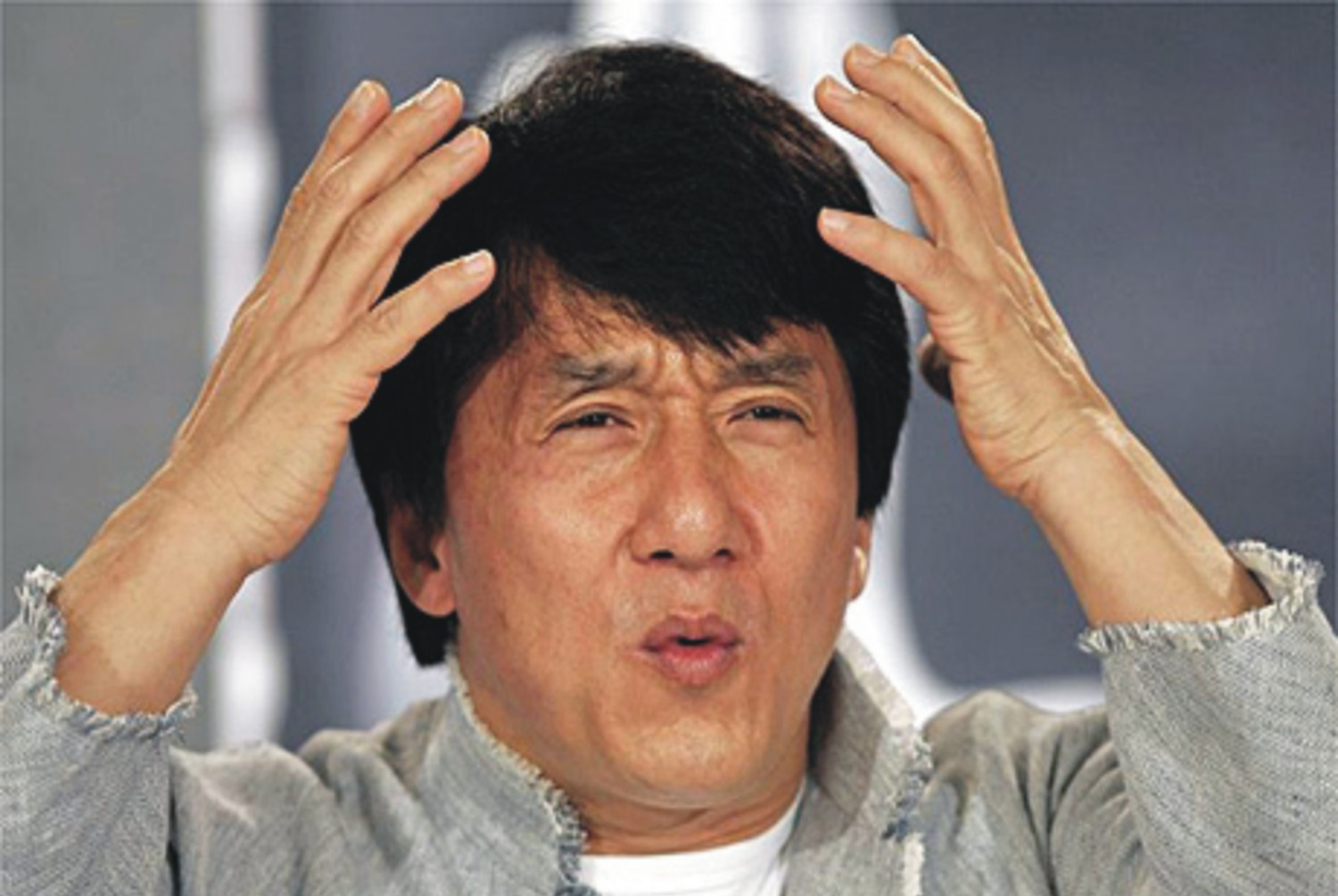

The song has a particular significance for this England team, as it was released back in ’96 when Gareth Southgate, England’s current manager and former English footballer, missed a decisive penalty that knocked his team out of the UEFA European Championship (Euros). Southgate has admitted that, for years, he hated the song as it reminded him of the time he had failed the nation. Now, Southgate has become a national hero again, taking a young and unlikely team to the brink of world cup glory. Quite funnily, laddish football fans have also adapted a 90’s Atomic Kitten pop tune to make a tongue-in-cheek version of it dedicated to their relationship with Gareth Southgate. His is a redemption story – a narrative that fans of Pakistani cricket, with our Mohammed Aamir’s and our constant battles against external adversities such as corruption, nepotism and terrorism, will recognise all too well.

Sadly for Southgate and the entire English nation, their team was knocked out this week. But English fans are generally heartened. They believe in their team again. They sang and danced together, inanely supporting a team certainly not full of world-beaters, but a team that is their team. Of course, there was a darker side to it as well, with brawls and anti-social behaviour breaking out in various cities when England lost. But from the land of burning effigies and broken TV sets, perhaps this darker side of passion is quite familiar as well.

The world cup is not coming home this time around. English fans are ‘gutted’. The 101-year-old woman must be distraught. Nonetheless, 2018 was the year that England rediscovered their jazba, the year that football finally came home.