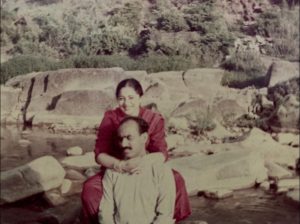

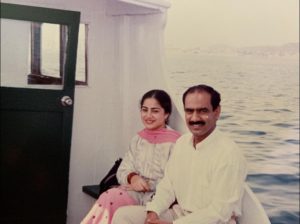

KARACHI: The story begins with her adoption, but much of what leads to the story happened earlier. It was a fine spring evening in Europe, in a city close to the airport. So close that we could see airplanes landing. I went to the bridge, the conning position of the ship, and noticed my wife, Farah standing on one of the wings. Her elbows resting on the wooden rails, and her chin resting on her palms. I went closer and asked, “enjoying the sight?” When I didn’t get any answer, I looked at her and noticed tears dripping down her cheeks. I asked her, “why? what’s the matter?” At first, she said nothing. Then on my insistence, she said, “It has been about six years to our marriage and I am here, standing on the bridge of a ship, counting airplanes touching down when I should be looking after a baby.” I took a few seconds to answer, but then I said, “well, we are doing what we can, and we are probably moving in the right direction. Hopefully, we will have a child someday.”

We got married in the spring of 1989, and about three months later I went to the ship, my wife accompanying me. We stayed there for a while and enjoyed the perks of a career that is all about sailing, traveling, exploring. In a few months, my wife was pregnant and it brought immense joy to our lives.

Unfortunately, our happiness did not last long because her pregnancy ended in a miscarriage. We were in China. After China, I went to Singapore and she had to sign off to rest. Later on, in September of 1991, we went to the UK for my Chief Officer’s exam as well as classes. By that time, she had had two miscarriages. We went to a doctor there, who told us my wife was too young – 23 years old, there was nothing to worry about.

My wife still jokes about how our eldest daughter is soon turning 25, a journalist focused on her career and independence, yet she herself was too busy worrying about children at a younger age. Fortunately, times have changed but earlier, family pressures soured the wounds that would have hurt a little less without the interference. What followed was nothing short of inconvenience. The urge to have a child resulted in my wife getting prescribed Clomid to enhance her fertility. At first, she took 1 tablet a day. Soon she changed it to two tablets a day and ended up with cysts in her ovaries. She underwent surgery to get them removed, which complicated things even further.

After a few miscarriages and surgeries, we tried to convince each other to seek adoption. At first, she hesitated. But then I explained that by adopting a child she’ll get busy, which may help with her depression as well as fertility. But where to adopt from? We wanted a child from within the family. That way we’d know where the child comes from, biologically for any formalities the child has to later undergo in life, such as in our Nikkah, where consent is required from biological parents. Farah’s family was out of the question. One of the many notions of patriarchy, although she was never ill-treated, she was also given a cold shoulder because she could not conceive, she feared hostility towards the child had it been from her side of the family. The obsession of passing on your genes to the future is quite common in desi families, and I was the only son, expected to continue the lineage. So we decided we’d take someone from my side of the family.

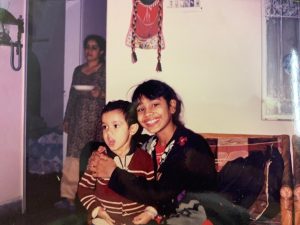

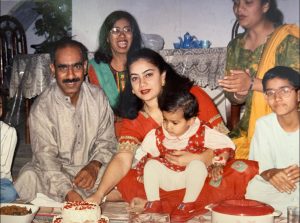

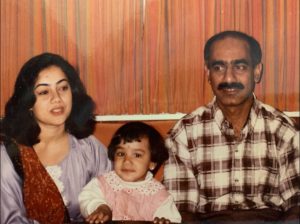

We went to the UK for my Captain’s exam. Upon reaching, we got a call from my family. My sister Rabab had given birth to a baby girl and she wanted us to adopt her as our own. Farah flew from England back to Karachi right away, while I stayed back to give my Captain’s exam. Hareem was only 40 days old when a ceremony was arranged by my family commemorating her adoption. It was not formal, because nothing was written down, but Rabab put the baby in Farah’s lap. And it has been since then that Hareem has been looked after by Farah, who she calls “mamma”. On the other hand, I became “papa”.

A lot of questions arose later. But we decided Hareem will not be given a new, false identity. She would still be Hareem, daughter of Rabab and Razi who birthed her. But the problem was that her little mind had a lot of room for questions. How to tell a small child that the person who is looking after you is not really your father and your mother? That would be too, too early. We gave her a maiden name instead of my name or Razi Bhai’s. She became Hareem Fatima. My daughters, who came afterward would follow suit. Although we reluctantly resorted to using our names as parents at her school. When she was an adolescent, we still thought it was too early for her to find out, but Hareem was becoming more aware.

There would be whispers amongst the family, and some would even say it out loud. “This is Areej, Rizwan and Farah’s eldest. Oh, and that is Hareem, they adopted her.” Sometimes, people would say it in front of Hareem. Initially, Hareem would be too occupied as a child to pay attention, but as she grew, questions sprung up. People always wanted to say things everyone already knew. reinforce open secrets. This was in bad taste and with a lack of any empathy towards us or Hareem. Why would they do that, we’d often ask ourselves? What catharsis did they gain? What personal insecurities are they satisfying? Why could they not see a child secure and happy? The family members who had urged Hareem’s adoption, were the ones now urging her to be sent back, almost as if no human feelings were involved.

Farah and I became afraid of losing her. “I wish she was our own,” Farah would tearfully tell me. “In flesh and blood.” I would listen quietly, holding my own tears back. Hareem ultimately did find out and hoarded resentment towards us for a few months, until things got better with time. Poisoned with information and fueled by assumptions, Hareem found herself amongst people who simply wanted her to stay with Rabab and not go back to her adoptive parents. Why that was, is a story for another day. However, Farah and I always wanted her to alternate between the two pairs of parents, and know that both parents would be there for her. Rabab had her own reasons for giving Hareem to us, some of them very personal and valid. So Hareem’s adoption, although done to make our own lives easier, made us learn to make it about her.

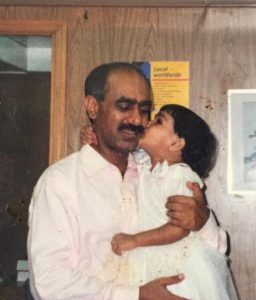

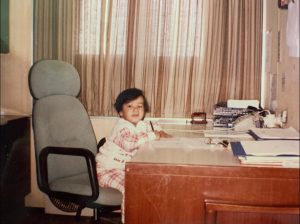

Hareem, although my adopted daughter, was the first child I had. The first excitement I had as a father when she learned to say ‘papa’, her first steps, and the faces she made as a baby when we gave her a little bit of coca-cola. When she found out at age thirteen, we feared her personality would not be complete seeing how her story was not the standard family life most kids get. Her adoption made her a special case and maybe, that might not let her blend in.

However, looking at her today, I see a complete, whole young woman. Determined, sometimes too determined (I am smiling as I write this). Standing out in the face of monotony. I hope Hareem comes back to this piece someday and remembers her adoption was in good faith, and also pray she plans her life ahead as I have always taught her to. Although it does reflect in her ways that she values pre-planning with all her core, something that reminds me of myself.

Designed by Aamir Khan

Designed by Aamir Khan