KARACHI: In Karachi, the sea closes in on us every summer. Balmy winds roam the streets, salty trails mark sweat licked skin and this listlessness finds a way of wrapping itself around the city.

Like every other woman growing up in Karachi, I was taught to self censor. Growing up, as I learned to navigate the behavioral expectations that were thrust upon me, I also learned to push myself to see that usually, I had a barely there, hard to recognise and not very ‘make-able’ choice. Exercising my right to that choice often resulted in dire societal consequences, but recognising and acknowledging the possibility of that ‘choice’ often felt like the first step towards resisting the gatekeepers of societal success who’d have me believe that ‘submission’ should be my aspirational lifestyle choice.

My privilege often protected me, and gave me the room to resist through recognising my own agency, but more often than not, I felt trapped in a salty listlessness, or I daresay, the self-fulfilling apathy of my personal Karachi hell: recognising my choices, being too afraid of making them, and suppressing that indecisiveness in order to get on with life.

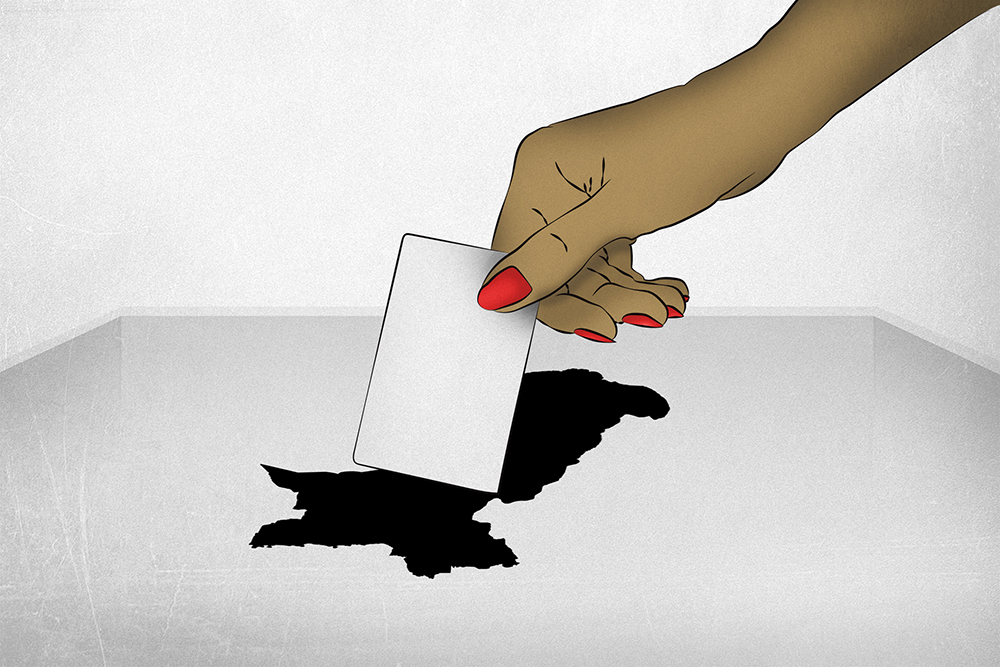

I’m voting tomorrow because for me, exercising my right to a choice is dissent.

And my indecisiveness was not just limited to the personal; our lack of ‘make-able’ choices is very much a political reality. We’re enveloped in a synthetically manufactured state of self-fulfilling apathy – perpetuated by establishments that govern us. As a woman, I’m often made to feel that having an opinion is unacceptable, talking politics and having political preferences is silly, and resisting, challenging, dissenting is criminal. And these rules don’t just apply to the length of my kameez or my morning debates with my Careem drivers – they cage my very existence in this city, as they are used to make me believe that nothing will change, that I must accept my reality and be grateful for the few choices I have as a ‘privileged’ woman.

Read: I’m a first-time voter but don’t see any point in voting

I’m voting tomorrow because for me, exercising my right to a choice is dissent. Participating in a system that perpetuates apathy – through the proliferation of misinformation, through fear tactics and intimidation, through control – and reminding that system that I know that I have the power to participate, is resistance.

However, to believe that our electoral democracy gives us a range of real choices would be foolish, to forget that it often perpetuates false narratives of nationhood and reifies the idea of a nation state that exists in the imagination of a few but is violently imposed on the rest would be unforgivable. A cursory glance at our political history shows us that we’re trapped between an overpowering military and weak political parties that function on the basis of dynasticism and patronage.

Perhaps the only thing that makes elections this time around different is a populist cricketer who’s need for validation from anyone, even the religious right, has made him put behind his ‘liberal’ days to get behind laws, institutions and ideas that oppress, suppress and endanger lives that are already unprotected by our state. Some are entertained by his politics, but many are willing to give his ‘newness’ a chance. While Imran Khan might not have initially entered our political systems through dynastic politics, his aspiration to power, at any cost, make him no different from an establishment that has exercised its power at the cost of our agency. And yet, Imran Khan’s presence in our electoral politics has made me want to vote. Behind his ‘Tabdeeli’ lies a sad truth: the alleged ‘new’ voice, in all its erraticness and outlandishness, has set up a political party with the same old goons.

Read: An A-to-Z guide to the General Elections

His presence this time around has made me look for real ‘new’ voices – and they exist: Ismat Shahjahaan, Ammar Rashid, Jibran Nasir, Sunita Parmar, Mohsin Dawar, Ali Wazir – new voices with platforms that address issues, such as women’s rights, worker’s rights and minority rights. Their voices challenge an establishment that has perpetuated apathy, that has made us feel powerless and ‘choiceless’. While some might argue that their ‘newness’ will hinder their ability to succeed, I believe that their presence in our electoral system, their ability to question and challenge and demand for us, gives us the opportunity to engage with and to participate in a system that has previously made us feel powerless.

I will show up, even if only to remind myself that I have a choice

In the buildup to the elections, I had the privilege of witnessing the mobilisation of the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement. As we organised ourselves to assist them, an older feminist told me that we have a lot more to gain from them, than they do from us. As the weeks progressed, her words rang true – I learned that people show up, even when the establishment attempts to ensure they don’t. PTM showed me that even in the face of extreme injustice – we, the people, have the power to demand accountability. And perhaps the first step towards demanding that accountability lies in our ability to recognise our power as a collective, to imagine ourselves as a community that has the power to dissent, resist and hold the systems that govern it accountable. And once we’ve managed to recognise that power, we must also find a way to perform it – we must ‘show up’.

I will show up, even if only to remind myself that I have a choice, I have the ability to resist that salty summer listlessness, that personal Karachi hell that is my self-fulfilling apathy. And as I participate in the performance of our collective power, I hope the state is reminded of the fact that it serves us, and that we have the power to hold its institutions and its representatives accountable – we are here, we are aware and we will participate.

Design by Aamir Khan

Design by Aamir Khan