KARACHI: Vitiligo is not contagious, or life-threatening. It is however a source of distress among people who have it in most closed-minded societies that not only refuse to normalize the condition but sometimes find over the top, superficial ways to their tokenism once they do finally address it. One such example of vitiligo appropriation was a recent photoshoot by fashion photographer Najam Mahmood, who faked vitiligo on a model.

View this post on Instagram

This is not the first time work such as this has sprung up from Mahmood. He has given his models dreadlocks and blackface in the past as well.

View this post on Instagram

Both these skin types are majorly alienated within Pakistani society. As far as vitiligo is concerned people have looked at the condition as a defect, a deficiency. So in order to normalize it to such a society, the idea has already failed if a model without the condition is being used to represent it. You’re pushing forward the narrative that even to represent the very condition, we need someone without the condition to do it.

To fully understand how the appropriation of vitiligo can affect individuals who have it, I spoke to Yusra Jamal, an active advocate who has instilled her determination towards normalizing vitiligo through her social media and a recently published personal essay.

View this post on Instagram

Jamal has often recounted her experiences growing up with vitiligo. How people without the condition had unsolicited advice ready and running each time they saw her.

“I don’t think people with my condition are represented at all. I was thinking about it, this morning only. There are hardly any actors, celebrities, or public figures with vitiligo in Pakistani media. Neither a man nor a woman or a child.” she says. “The media barely wants to acknowledge that we exist. They refuse to see it as something entirely normal and beyond our control.”

Her last point makes me wonder. The media wants to keep things under its control. This is probably why they use models they can erase the condition from, be it vitiligo or black face. Their appropriation of vitiligo, I’m assuming, in their own heads seems like a favor to the ones who have it. They do it while inhibiting their representation in exchange with someone without the condition.

“I feel different every day. Some days I feel great. I think to myself thank God I have this, and I am pretty. I feel okay about myself because I never truly saw myself without my vitiligo. It is when I meet certain people in my life that remind me of how unaccepted my condition is,” says Jamal talking about how she is made to feel about her skin. “People stare at me like I ran away with their dog, or slapped their kid. When there are rishta related conversations, all they care about are my marks. Aapki bachchi kay mu par dhabbay hein (your daughter has spots on her face). Those dhabbay are not my fault or my parents’.”

View this post on Instagram

“If you truly want to promote vitiligo as a normal skin condition, and tell people that it is fine to have it. That they should own their skin etc., why do they not use people who already have it? I don’t understand the concept of finding someone who does not have it, and then painting the condition onto that person to show it is okay to have that condition,” she expresses. “What are you trying to even say? Everyone knows that the model does not have vitiligo. Bring someone who has it, and tell the world how comfortable that model can be in her skin.”

Jamal urges people to accept their vitiligo because without having yourself on your side, it is just war within yourself. “It is like wearing clothes you’re not comfortable in. You step outside and everyone will sense your discomfort. I understand it is not easy to accept yourself, particularly on days when you see yourself misrepresented. You think ‘why me?’ or ‘am I even lovable?’ But to really have someone else love you, you have got to love yourself first.”

“Society is very far from accepting that vitiligo is a normal condition. For society, a set of rigid rules are in place and everything else is villainized. Like dark skin is bad, fair skin is beautiful,” she laments. “I don’t think we are at the point of accepting this condition even in the coming twenty years. Ten years ago people stopped me in my tracks in a similar fashion as they do today. They’d ask, and then list down remedies to get rid of it. The only thing that has changed is how I view myself now. I am beautiful – that is all that matters.”

View this post on Instagram

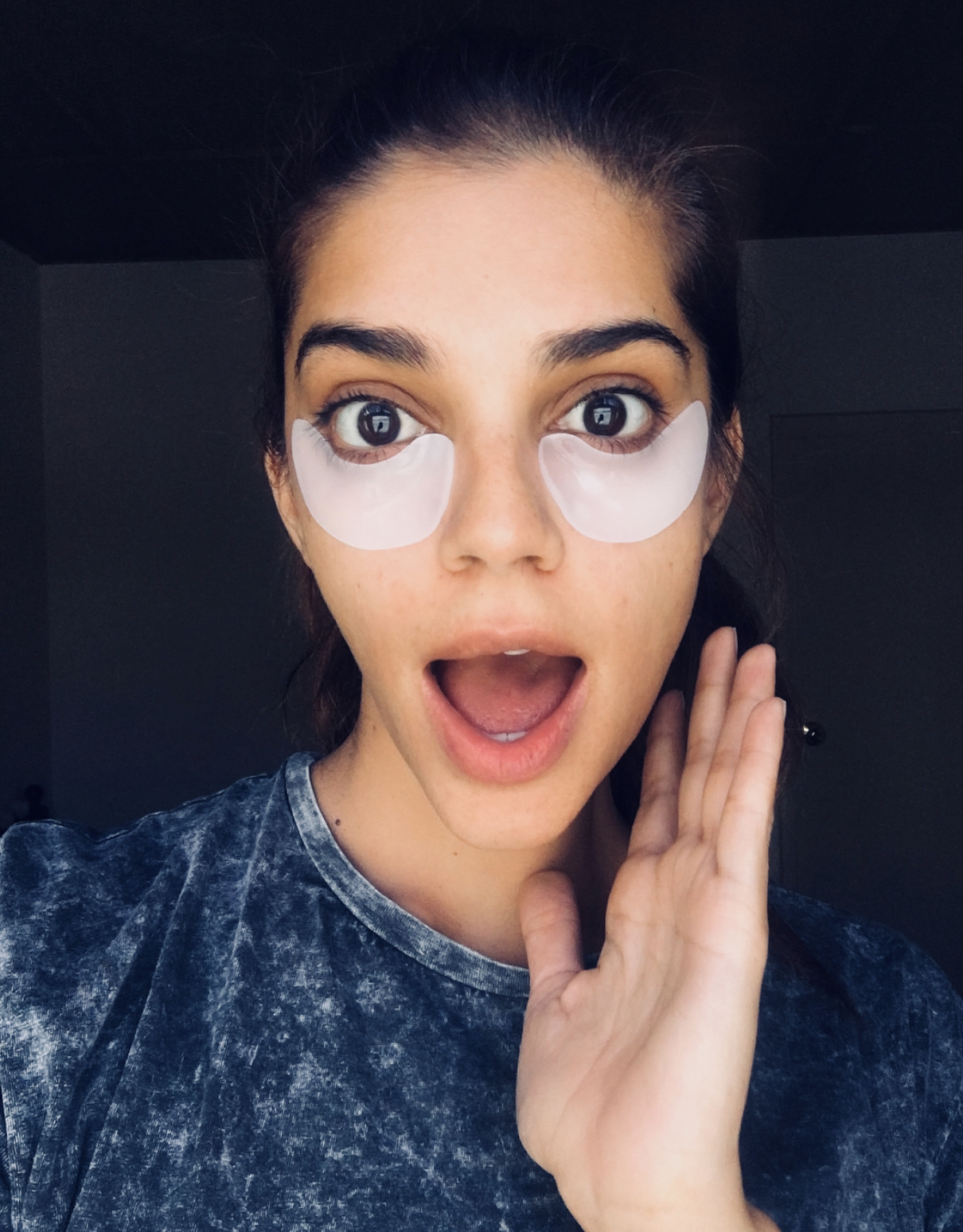

An appropriated model from Najam Mahmood’s recent shoot – SKY AND THE SOUL

An appropriated model from Najam Mahmood’s recent shoot – SKY AND THE SOUL