KARACHI: Through her passion, documentary filmmaker Haya Fatima Iqbal establishes that a woman’s aptitude for learning and excelling has the power to elevate her role in a patriarchal society.

“I’ve seen all women in my family as go-getters.” Returning from the kitchen to resume the interview, Haya apologizes. She heartily laughs at her own quip about the crucial iftar preparations, very much living up to our expectations of her as an all-rounder.

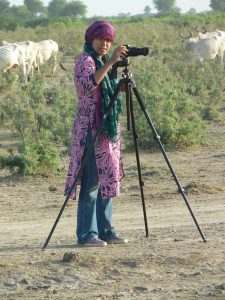

One would assume that a country-wide lock down interfered with Haya’s travel plans to another semi-urban location hiding an unsung hero. What inhibitions does a lock down bring for someone who has shot in over 40 towns of the country? Invincibly, one April morning, she managed to reach another shooting site, a mosque in Karachi, carrying the usual four-bag luggage of equipment. The PPE must be an unfortunate addition to the gear this time.

Growing up

“I grew up watching influential women on both my paternal and maternal side,” says Haya who acknowledges her family’s influence as her career’s backbone and is grateful for this privilege that many crave. “Unconventional jobs were a norm. One of my aunts worked as a commando-trained, airport security officer all her life. She dashed to hug me one time I went to shoot at the airport. An aunt and niece in embrace, holding their gun and camera respectively must have been an unusual sight.”

Haya took great delight in her job as an assistant producer and later a producer at SOC Films. Her films co-produced with Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy, A Girl in a River and Armed with Faith were Emmy winners. And her career had reached a crescendo when she craved change. Her decision to quit SOC films was undeniably driven by a purpose. “At one point, my growth had stopped because our job responsibilities were specific. I was ready to venture outdoors independently.” Laughing off all praises, she retires to earth again, claiming that the brave nerve is no talent of her own. She attributes the choice to the brilliance of her hands-on Master’s program at NYU.

Whatever little inhibitions or traces of being a comfort-loving Pakistani girl remained in her, were washed away while hustling in the streets of New York. Now, Haya is the producer, director and cinematographer alone of 23 documentary films in Pakistan.

Fight for equality

She didn’t think twice before admitting that she is a feminist. The temperature drops a degree in the conversation as she expresses her disgust over the notion of ‘constitutionally provided rights’ that our society adheres to. “These rights are no good on paper if they cannot be practically applied. Issuing an FIR complaint is still an impossibility for women and so is visiting the court.”

It is not puzzling that Haya is rallying women to fight for their equal rights without having any record of demonstrating, campaigning or testifying. Her advice isn’t covert and it boldly reflects in her performance. Being an independent, woman filmmaker, she bears the brunt of it but meagerly. Her reason for never facing gendered violence or hatred is the caution and conduct. “It’s because we have our guard held so high already. And it’s stressful. Those walls we journalists and reporters have built around us are so high, it stops the predator in their tracks before even attempting,” Her voice tenses as she admits, “In an ideally safe society, these walls must not exist.”

Read: Unintended sacrifices: Books recounting the plight of women during partition

Visiting every nook and cranny of Pakistan exposed the different ways in which men welcomed her. Some act surprised upon noticing Haya does not have an assistant by her side. “I tell them I am my own assistant. With time I notice that they adapt to the fact that I can operate my equipment without masculine help,” She tells us. “Another way is by challenging your stamina. They would persistently offer you a seat if you’re waiting for someone at an office. Or try to remove you from the center of action if you are observing a quarrel. I have to calmly remind them that if I sat, my task wouldn’t transpire as smoothly as it should.” She sees their disturbance pacifying automatically then.

The documentary filmmaker’s tone relaxes as she tells us, “I can predict it before it happens now.” The way she tackles it, she says, is by following the rules. She is confident that as long as she rules the roost in the field, she is making a contribution.“ I am willing to make these sacrifices and if the end result is to make a bigger change that is to stand in the middle of a street with a camera on my shoulders, then I’m also willing to wear a wide dupatta and loose jeans.”

Haya reminds us how even in privileged households, mothers ask us to put on a dupatta, visiting a certain household. If our extended family friends and family circles have such double, triple standards, then imagine the amount of thought a filmmaker would have to put in deciding what clothes to where while visiting a rural neighborhood, a government office, a military office, a mosque.

Haya’s approach is not intricate. In fact it’s one based on experience and a tremendous amount of patience. She assured me, “The big feather that I want to ruffle right now is to ensure the next time you go into the field two years down, no one eyes you as an alien. They’d have already seen me working tirelessly in jeans and cropped hair on the streets. That’s what can be my contribution to our fight. You can continue the fight by breaking another stereotype. This way we’ll foster a new normal for Pakistani women every decade.”

In conclusion, Haya thinks its necessary to find the balance between breaking stereotypes and following rules. “If I’m at the best of my behaviour at work, at the same time making a change by being present there, I’ll leave a good impression of women in the media after I’ve left.” This statement might be problematic for people but Haya staunchly beliefs that it’s a slow fight. “We are supposed to hold up angry posters at Aurat March some days. But other times you can also be softer in your approach. You can operate with care and coolness to make people think differently about women.”